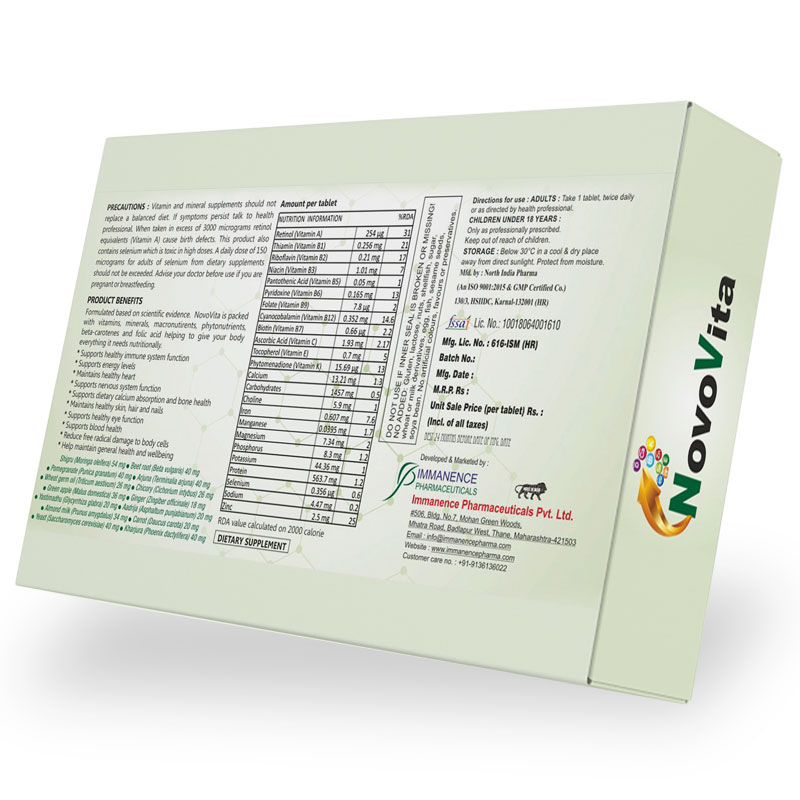

NovoVita

- Brand:NovoVita

-

M. R. P. : 375.00

- (INCL. ALL TAXES)

Free Delivery for orders over Rs. 1500/-

NovoVita

- 100% Natural

- Vitamins + Minerals + Macronutrients

- Daily Health Supplement and Nutritional Support

- Helps Support Energy Production

Formulated based on scientific evidence. NovoVita contains a comprehensive blend of 15 specifically selected natural, nutrient-rich herbs to provide daily nutritional support. NovoVita is packed with vitamins, minerals, macronutirents, phytonutrients, beta-carotenes and folic acid helping to give your body everything it needs nutritionally.

Shigru (Moringa oleifera)

It is believed that the moringa tree originated in northern India and is being used in Indian medicine for around 5000 years, and there are also accounts of it being utilized by the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians. The plant is referred by several names such as horseradish tree, drumstick tree, ben oil tree, miracle tree, and “Mother’s Best Friend”. It is a drought-tolerant, fast-growing, multi-purpose and one of most useful tree due to its medicinal and nutritional properties and is therefore referred as a ‘miracle tree’. Different parts of this plant are used for the management of anemia, urinary tract infections, kidney stones, arthritis and joint disorders and high blood pressure. Its leaves are potent source of Vitamins A, B and C, minerals (iron and calcium) and proteins.

Beet Root (Beta vulgaris)

The prehistoric root vegetable originates from the coastlines of North Africa, Europe, and Asia. But the food has become popular worldwide, thanks to its sweet flavour and powerful health benefits. The leaves and roots of beets are packed with nutrition, including antioxidants that fight cell damage and reduce the risk of heart disease. Beets are one of the few vegetables that contain betalains, a powerful antioxidant that gives beets their vibrant colour. Betalains reduce inflammation and may help protect against cancer and other diseases. Beets are rich in folate (Vitamin B9) and potassium which helps cells grow and function. Folate plays a key role in controlling damage to blood vessels, which can reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke. Beets are also excellent source of Vitamins A , B1, B2, B6, B12 and C, and manganese.

Pomegranate (Punica granatum)

Pomegranates have been used for years for their health benefits. Modern science has found that pomegranates can help protect your heart and may even prevent cancer. Pomegranates can have up to three times more antioxidants than green tea or red wine. Antioxidants protect cells from damage, prevent diseases and reduce inflammation and the effects of aging. Pomegranate is a rich source of Vitamins B5, B6, C, and K and also contains Vitamin E in small amounts. In addition, it is a rich source of minerals (potassium and copper).

Arjuna (Terminalia arjuna)

Arjuna also known as the “Arjun tree” is a widely grown in India. It has various medicinal effects including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. Arjuna helps reduce the risk of heart diseases. It strengthens and tones the heart muscles and helps in proper functioning of the heart. Arjuna tree also has strong anti-hypertensive property and helps reduce high blood pressure. Arjuna has an ingredient which helps in absorption of Calcium and other minerals and plays key role similar to Vitamin D.

Wheat germ oil (Triticum Vulgare)

Wheat germ oil is a highly nutritional product, which contains about 10–15% lipids, 26–35% proteins, 17% sugars, 1.5–4.5% fibre and 4% minerals. Germ contains approximately 11% oil, also with considerable amount of bioactive compounds. Wheat germ oil is the one with the highest tocopherol content among vegetable oils. In addition, the ratio of polyunsaturated fatty acids, mainly linoleic and linolenic acids, is quite high (almost 80% of the oil). Wheat germ oil has amazing benefits for the skin as it is rich in vitamin A, as well as lecithin, minerals, protein, and vitamins B1, B2, B3, B6, and E.

Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

Chicory root has a mild laxative effect, increases bile from the gallbladder, and decreases swelling. Chicory is a rich source of beta-carotene. Inulin is a type of fiber known as a fructan or fructooligosaccharide, a carbohydrate made from a short chain of fructose molecules that our body doesn’t digest. It acts as a prebiotic and feeds the beneficial bacteria in our gut. These helpful bacteria play a key role in reducing inflammation, fighting harmful bacteria, and improving mineral absorption. Chicory root contains many different nutrients, including calcium, phosphorus, potassium, and folate. It also supplies limited amounts of magnesium, vitamin A, and vitamin C.

Green apple (Malus domestica)

Green apples have a lot of health and beauty benefits to offer. They are packed with nutrients, fiber, minerals, and vitamins that are good for the overall health. Green Apple contains a large concentration of flavonoids, as well as a variety of other phytochemicals, and the concentration of these phytochemicals may vary on many factors, such as cultivar of the apple, harvest and storage of the apples, and processing of the apples. Concentration of phytochemicals also varies greatly between the apple peels and the apple flesh. Green apples are good source of Vitamins A and C, calcium and iron.

Ginger (Zingiber officinale)

Ginger root comes from the Zingiber officinale plant, and it has been used in Chinese and Indian medicine for thousands of years. Ginger helps to relieve nausea and vomiting and aid in digestion. Antioxidants and other nutrients in ginger root may help prevent or treat arthritis, inflammation, and various types of infection. Ginger is a nutrient powerhouse, containing a wide range of vitamins – including vitamin C, and B vitamins thiamine, riboflavin and niacin – along with minerals such as iron, calcium and phosphorus.

Yashtimadhu (Glycyrrhiza glabra)

The main chemical component of yashtimadhu is glycyrrhizin (about 2-9%), a triterpene saponin with low haemolytic index. Glycyrrhetinic (glycyrrhetic) acid (0.5-0.9%), the aglycon of glycyrrhizin is also present in the root. Other active constituents include phytosterols, isoflavonoids, chalcones, coumarins, triterpenoids and sterols, lignans, amino acids, amines, gums, mineral salts (such as calcium, phosphorus, sodium, potassium, iron, magnesium, silicon, selenium, manganese, zinc, and copper), vitamins (B1, B2, B3, B5, C and E) and volatile oils. Its main. Benefits include antacid, anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial properties, controls cholesterol and boosts immunity.

Adrija (Asphaltum punjabianum)

Preclinical investigations on Adrija indicate its great potential uses in certain diseases, and various properties have been recognised, including antiulcerogenic properties; antioxidant properties; cognitive and memory enhancer; antidiabetic properties; anxiolytic; antiallergic properties and immunomodulator, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antifungal properties. Adrija contains fulvic acid and more than 84 minerals and 1/2 teaspoon of provides 30%, 4%, 4% and 3% daily value of iron, calcium, selenium and zinc respectively.

Almond milk (Prunus amygdalus)

Almond milk is reported to be as a nutritious food with a 100-gram serving providing more than 20% of the daily value of riboflavin, niacin, vitamin E, calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, and zinc. The same serving size is also a good source (10-19% RDI) of thiamine, vitamin B6 and folate, choline, and potassium. They are also rich in dietary fiber, monounsaturated fats and polyunsaturated fats which potentially may lower LDL cholesterol. Typical of nuts and seeds, almonds also contain phytosterols such as beta-sitosterol, stigmasterol, campesterol, sitostanol and campestanol, which have been associated with cholesterol-lowering properties

Carrot (Daucus carota)

Carrots are a multi-nutritional food source. They are an important root vegetable, rich in natural bioactive compounds, which are recognised for their nutraceutical effects and health benefits. The four types of phytochemicals found in carrots, namely phenolics, carotenoids, polyacetylenes, and ascorbic acid, are noted. These chemicals aid in the risk reduction of cancer and cardiovascular diseases due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, plasma lipid modification, and anti-tumour properties. Carrots are excellent source of Vitamins, A, B6, and K, calcium, iron, biotin and potassium.

Nutritional yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)

Yeasts are used in preparation of human foods and beverages, where they besides having technological functions, confer different beneficial effects on human health and well-being. Among these, the most well-known is the probiotic effect. Alongside the role as probiotics, yeasts have other beneficial functions such as dephosphorylation of phytate and folate biofortification of foods. By choosing appropriate yeast strains as starter cultures and using optimized food processing techniques, it is possible to improve the nutritional value of foods in general. Fortified nutritional yeast is especially rich in B vitamins, including thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), and B6 and B12. Trace minerals including zinc, selenium, manganese, and molybdenum, which are involved in gene regulation, metabolism, growth, and immunity

Kharjura (Phoenix dactylifera)

Date flesh is found to be low in fat and protein but rich in sugars, mainly fructose and glucose. It is a high source of energy, as 100g of flesh can provide an average of 314 kcal. Ten minerals were reported, the major being selenium, copper, potassium, and magnesium. The consumption of 100g of dates can provide over 15% of the recommended daily allowance from these minerals. Vitamins B-complex and C are the major vitamins in dates. High in dietary fiber (8g/100g), insoluble dietary fiber was the major fraction of dietary fiber in dates. Dates are a good source of antioxidants, mainly carotenoids and phenolics. Date seeds contain higher protein (5.1g/100g) and fat (9g/100g) as compared to the flesh. It is also high in dietary fiber (73.1g/100g), phenolics (3942 mg/100g) and antioxidants (80400 micromol/100 g).

Nartaka (Eleusine coracana)

Millets are also a gluten-free food, commonly used like porridge. Nutritional value of the seeds is as follows: 100g of edible part of seed (at 12% moisture) contains 7.7g protein, 1.5g fat, 2.6g ash, 3.6g crude fiber, 72.6g carbohydrates, 350mg Calcium, 3.9mg Iron, 0.42mg thiamine, 0.19mg riboflavin, and 1.1mg niacin and 1406 KJ of energy value. The husk forms 5.6% of the weight of the grain. The grain is higher in protein, fat, and minerals (calcium, iron, and phosphorous), relative to rice, corn, and sorghum. Finger millet is full of dietary fiber, which helps to control the bad cholesterol that can contribute to heart diseases like atherosclerosis. Soluble fiber absorbs cholesterol before it enters your bloodstream, maintaining a lower cholesterol level without medication.

Adults:- Take 1 capsule, twice daily or as directed by health professional.

Children Under 18 years:- Only as professionally prescribed.

Storage:- Below 30°C in a cool & dry place away from direct sunlight. Protect from moisture.

Precautions:- Vitamin and mineral supplements should not replace a balanced diet. If symptoms persist talk to health professional. When taken in excess of 3000 micrograms retinol equivalents (Vitamin A) cause birth defects. This product also contains selenium which is toxic in high doses. A daily dose of 150 micrograms for adults of selenium from dietary supplements should not be exceeded. Advise your doctor before use if you are pregnant or breastfeeding.

References:

- Fahey, J.W., 2005. Moringa oleifera: a review of the medical evidence for its nutritional, therapeutic, and prophylactic properties. Part 1. Trees for life Journal, 1(5), pp.1-15.

- Shalini, S. and Shivaprasad, H.N., 2017. Moringa oleifera-Nutritional rich functional food. Int j Herb, 5, pp.83-86.

- Shivangini, P., Mona, K. and Nisha, P., 2022. Comprehensive Review: Miracle Tree Moringa oleifera Lam. Current Nutrition & Food Science, 18(2), pp.166-180.

- Chukwuebuka, E., 2015. Moringa oleifera “the mother’s best friend”. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences, 4(6), pp.624-630.

- Chhikara, N., Kushwaha, K., Sharma, P., Gat, Y. and Panghal, A., 2019. Bioactive compounds of beetroot and utilization in food processing industry: A critical review. Food chemistry, 272, pp.192-200.

- Ceclu, L. and Nistor, O.V., 2020. Red beetroot: Composition and health effects—A review. J. Nutr. Med. Diet Care, 6(1), pp.1-9.

- Kale, R., Sawate, A., Kshirsagar, R., Patil, B. and Mane, R., 2018. Studies on evaluation of physical and chemical composition of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.). International journal of chemical studies, 6(2), pp.2977-2979.

- Opara LU, Majeed RAA, Yusra SAS. Physico-chemical properties, vitamin C content and antimicrobial properties of pomegranate fruit (Punica granatum L.). Food and Bioprocess Technology. 2009; 2:315-321

- Suman, M. and Bhatnagar, P., 2019. A review on proactive pomegranate one of the healthiest foods. International Journal of Chemical Studies, 7(3), pp.189-194.

- Akhtar, S., Ismail, T. and Layla, A., 2019. Pomegranate bioactive molecules and health benefits. In Bioactive molecules in food (pp. 1253-1279). Springer, Cham.

- Amalraj A, Gopi S. Medicinal properties of Terminalia arjuna (Roxb.) Wight & Arn.: A review. J Tradit Complement Med. 2016 Mar 20;7(1):65-78. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.02.003. PMID: 28053890; PMCID: PMC5198828.

- Soni, Neelam & Singh, Vinay. (2019). Efficacy and Advancement of Terminalia arjuna in Indian Herbal Drug Research: A Review. Trends in Applied Sciences Research. 14. 233-242. 10.3923/tasr.2019.233.242.

- Gupta, R., Singhal, S., Goyle, A. and Sharma, V.N., 2001. Antioxidant and hypocholesterolaemic effects of Terminalia arjuna tree-bark powder: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 49, pp.231-235.

- Chaudhari, G.M. and Mahajan, R.T., 2015. Comprehensive study on pharmacognostic, physico and phytochemical evaluation of Terminalia arjuna Roxb. stem bark. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 4(3), p.186.

- Brandolini, A. and Hidalgo, A., 2012. Wheat germ: not only a by-product. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 63(sup1),

- Dunford, N.T., 2012. 1 Traditional and Emerging Feedstocks for Food and Industrial Bioproduct Manufacturing. Food and Industrial Bioproducts and Bioprocessing, p.1.

- Zou, Y., Gao, Y., He, H. and Yang, T., 2018. Effect of roasting on physico-chemical properties, antioxidant capacity, and oxidative stability of wheat germ oil. LWT, 90, pp.246-253.

- Ghafoor, K., Özcan, M.M., AL‐Juhaımı, F., Babıker, E.E., Sarker, Z.I., Ahmed, I.A.M. and Ahmed, M.A., 2017. Nutritional composition, extraction, and utilization of wheat germ oil: A review. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, 119(7), p.1600160.

- Evans, H.M., Emeeson, O.H. and Emerson, G.A., 1936. The isolation from wheat germ oil of an alcohol, α-tocppherol, having the properties of vitamin E. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 113, pp.319-332.

- Flamm, G., Glinsmann, W., Kritchevsky, D., Prosky, L. and Roberfroid, M., 2001. Inulin and oligofructose as dietary fiber: a review of the evidence. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 41(5), pp.353-362.

- Franck, A., 2002. Technological functionality of inulin and oligofructose. British journal of Nutrition, 87(S2), pp.S287-S291.

- Chikkerur, J., Samanta, A.K., Kolte, A.P., Dhali, A. and Roy, S., 2020. Production of short chain fructo-oligosaccharides from inulin of chicory root using fungal endoinulinase. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology, 191(2), pp.695-715.

- Nwafor, I.C., Shale, K. and Achilonu, M.C., 2017. Chemical composition and nutritive benefits of chicory (Cichorium intybus) as an ideal complementary and/or alternative livestock feed supplement. The Scientific World Journal, 2017.

- Patocka, J., Bhardwaj, K., Klimova, B., Nepovimova, E., Wu, Q., Landi, M., Kuca, K., Valis, M. and Wu, W., 2020. Malus domestica: A review on nutritional features, chemical composition, traditional and medicinal value. Plants, 9(11), p.1408.

- Violeta, N.O.U.R., Trandafir, I. and Ionica, M.E., 2010. Compositional characteristics of fruits of several apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) cultivars. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca, 38(3), pp.228-233.

- Ampomah-Dwamena, C., Dejnoprat, S., Lewis, D., Sutherland, P., Volz, R.K. and Allan, A.C., 2012. Metabolic and gene expression analysis of apple (Malus× domestica) carotenogenesis. Journal of experimental botany, 63(12), pp.4497-4511.

- Anh, N.H., Kim, S.J., Long, N.P., Min, J.E., Yoon, Y.C., Lee, E.G., Kim, M., Kim, T.J., Yang, Y.Y., Son, E.Y. and Yoon, S.J., 2020. Ginger on human health: a comprehensive systematic review of 109 randomized controlled trials. Nutrients, 12(1), p.157.

- Nikkhah Bodagh, M., Maleki, I. and Hekmatdoost, A., 2019. Ginger in gastrointestinal disorders: A systematic review of clinical trials. Food science & nutrition, 7(1), pp.96-108.

- Shirin, A.P. and Jamuna, P., 2010. Chemical composition and antioxidant properties of ginger root (Zingiber officinale). Journal of Medicinal Plants Research, 4(24), pp.2674-2679.

- Anagha, K., Manasi, D., Priya, L. and Meera, M., 2014. Antimicrobial activity of yashtimadhu (glycyrrhiza glabra L.)-a review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci, 3(1), pp.329-336.

- Giri, A., Bera, A., Giri, D. and Das, B., 2021. Boosting Immunity by Liquorice (Yashtimadhu) in COVID-19 Pandemic Situation. In Immunity Boosting Functional Foods to Combat COVID-19 (pp. 53-60). CRC Press.

- Anagha, K., Manasi, D., Priya, L. and Meera, M., 2012. COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW ON HISTORICAL ASPECT OF YASHTIMADHU-GLYCYRRHIZA GLABRA L. Global Journal of Research on Medicinal Plants & Indigenous Medicine, 1(12), p.687.

- Babich, O.O., Ulrikh, E.V., Larina, V.V. and Bakhtiyarova, A.K., 2022. Study of the composition and properties of extracts of Glycyrrhiza glabra grown in the Kaliningrad region and prospects of its use. Food systems, 5(3), pp.261-270.

- Karkanis, A., Martins, N., Petropoulos, S.A. and Ferreira, I.C., 2018. Phytochemical composition, health effects, and crop management of liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.): Α medicinal plant. Food reviews international, 34(2), pp.182-203.

- Carrasco-Gallardo, C., Guzmán, L. and Maccioni, R.B., 2012. Shilajit: a natural phytocomplex with potential procognitive activity. International Journal of Alzheimer’s disease, 2012.

- Agarwal, S.P., Khanna, R., Karmarkar, R., Anwer, M.K. and Khar, R.K., 2007. Shilajit: a review. Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives, 21(5), pp.401-405.

- Berryman, C.E., Preston, A.G., Karmally, W., Deckelbaum, R.J. and Kris-Etherton, P.M., 2011. Effects of almond consumption on the reduction of LDL-cholesterol: a discussion of potential mechanisms and future research directions. Nutrition reviews, 69(4), pp.171-185.

- Alozie Yetunde, E. and Udofia, U.S., 2015. Nutritional and sensory properties of almond (Prunus amygdalu Var. Dulcis) seed milk. World Journal of Dairy & Food Sciences, 10(2), pp.117-121.

- Sharma, K.D., Karki, S., Thakur, N.S. and Attri, S., 2012. Chemical composition, functional properties and processing of carrot—a review. Journal of food science and technology, 49(1), pp.22-32.

- Surbhi, S., Verma, R.C., Deepak, R., Jain, H.K. and Yadav, K.K., 2018. A review: Food, chemical composition and utilization of carrot (Daucus carota L.) pomace. International Journal of Chemical Studies, 6(3), pp.2921-2926.

- Leclerc, J., Miller, M.L., Joliet, E. and Rocquelin, G., 1991. Vitamin and mineral contents of carrot and celeriac grown under mineral or organic fertilization. Biological Agriculture & Horticulture, 7(4), pp.339-348.

- Nagraj, G.S., Jaiswal, S., Harper, N. and Jaiswal, A.K., 2020. Carrot. Nutritional Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Fruits and Vegetables, pp.323-337.

- Moslehi-Jenabian, S., Pedersen, L.L. and Jespersen, L., 2010. Beneficial effects of probiotic and food borne yeasts on human health. Nutrients, 2(4), pp.449-473.

- Jach, M.E. and Serefko, A., 2018. Nutritional yeast biomass: characterization and application. In Diet, microbiome and health (pp. 237-270). Academic Press.

- Al-Farsi*, M.A. and Lee, C.Y., 2008. Nutritional and functional properties of dates: a review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 48(10), pp.877-887.

- Rahmani, A.H., Aly, S.M., Ali, H., Babiker, A.Y. and Srikar, S., 2014. Therapeutic effects of date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera) in the prevention of diseases via modulation of anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and anti-tumour activity. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine, 7(3), p.483.

- El-Far, A.H., Oyinloye, B.E., Sepehrimanesh, M., Allah, M.A.G., Abu-Reidah, I., Shaheen, H.M., Razeghian-Jahromi, I., Noreldin, A.E., Al Jaouni, S.K. and Mousa, S.A., 2019. Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera): novel findings and future directions for food and drug discovery. Current drug discovery technologies, 16(1), pp.2-10.

- El-Sohaimy, S.A. and Hafez, E.E., 2010. Biochemical and nutritional characterizations of date palm fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.). J Appl Sci Res, 6(6), pp.1060-7. 49. Hulse, J.H., Laing, E.M. and Pearson, O.E., 1980. Sorghum and the millets: their composition and nutritive value. Academic press.

- Rao, M.S. and Muralikrishna, G., 2001. Non-starch polysaccharides and bound phenolic acids from native and malted finger millet (Ragi, Eleusine coracana, Indaf-15). Food Chemistry, 72(2), pp.187-192.

- Malleshi, N.G. and Klopfenstein, C.F., 1998. Nutrient composition, amino acid and vitamin contents of malted sorghum, pearl millet, finger millet and their rootlets. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 49(6), pp.415-422.

- Chandra, D., Chandra, S. and Sharma, A.K., 2016. Review of Finger millet (Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn): A power house of health benefiting nutrients. Food Science and Human Wellness, 5(3), pp.149-155.

SCIENTIFIC REFERENCES:

- Abenavoli L, Capasso R, Milic N, Capasso F. Milk thistle in liver diseases: past, present, future. Phytotherapy research : PTR. 2010;24(10):1423-32.

- Ferenci P, Dragosics B, Dittrich H, Frank H, Benda L, Lochs H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of silymarin treatment in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Journal of hepatology. 1989;9(1):105-13.

- Rambaldi A, Jacobs BP, Iaquinto G, Gluud C. Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C liver diseases--a systematic cochrane hepato-biliary group review with meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2005;100(11):2583-91.

- El-Kamary SS, Shardell MD, Abdel-Hamid M, Ismail S, El-Ateek M, Metwally M, et al. A randomized controlled trial to assess the safety and efficacy of silymarin on symptoms, signs and biomarkers of acute hepatitis. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology. 2009;16(5):391-400.

- Lieber CS, Leo MA, Cao Q, Ren C, DeCarli LM. Silymarin retards the progression of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis in baboons. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2003;37(4):336-9.

- Zhang W, Hong R, Tian T. Silymarin Protective Effects and Possible Mechanisms on Alcoholic Fatty Liver for Rats. Biomolecules & therapeutics. 2013;21(4):264-9.

- Salma U, Kundu S, Gantait S. Phytochemistry and Pharmaceutical Significance of Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth. 2017. p. 26-37.

- Qureshi H, Masood M, Arshad M, Qureshi R, Sabir S, Amjad MS. Picrorhiza kurroa: An ethnopharmacology important plant species of Himalayan region. Pure and Applied Biology. 2015.

- Sharma M, Rao C, Duda P. Immunostimulatory activity of Picrorhiza kurroa leaf extract. Journal of ethnopharmacology. 1994;41(3):185-92.

- Ross IA. Phyllanthus niruri. Medicinal Plants of the World: Volume 1 Chemical Constituents, Traditional and Modern Medicinal Uses. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2003. p. 393-403.

- Satya A, Narendra K, swathi j, sowjanya km. Phyllanthus niruri: A Review on its Ethno Botanical, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profile. journal of pharmacy research. 2012;5:4681.

- Paithankar V, Raut K, Charde R, Vyas J. Phyllanthus niruri: a magic herb. Research in Pharmacy. 2015;1(4).

- Lee NY, Khoo WK, Adnan MA, Mahalingam TP, Fernandez AR, Jeevaratnam K. The pharmacological potential of Phyllanthus niruri. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology. 2016;68(8):953-69.

- Patel HJ. Clinical Trials of Phyllanthus Amarus as Hepatoprotective and Their Market Formulations: Saurashtra University; 2009.

- Jain M, Kapadia R, Jadeja RN, Thounaojam MC, Devkar RV, Mishra SH. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Tecomella undulata– A review. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2012;2(3, Supplement):S1918-S23.

- Khatri A, Garg A, Agrawal SS. Evaluation of hepatoprotective activity of aerial parts of Tephrosia purpurea L. and stem bark of Tecomella undulata. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122(1):1-5.

- Bhatt N, Deshpande M, Namewar P, Pawar S. A Review of classical, proprietary and patented ayurved products and their ingredients in liver/spleen disease. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Research IJPSR. 2018;9(10):4056-70.

- Verma N. Journal of Drug Discovery and Therapeutics A brief study on zingiber officinale-A review. Journal of Drug Discovery and Therapeutics. 2015;3:20-7.

- Kaushik R. Trikatu-A combination of three bioavailability enhancers. International Journal of Green Pharmacy (IJGP). 2018;12(03).

- Mashhadi NS, Ghiasvand R, Askari G, Hariri M, Darvishi L, Mofid MR. Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of ginger in health and physical activity: review of current evidence. International journal of preventive medicine. 2013;4(Suppl 1):S36-42.

- Malik B, Rehman RU. Chicory Inulin: A Versatile Biopolymer with Nutritional and Therapeutic Properties. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Healthcare and Industrial Applications.373.

- Al-Snafi AE. Medical importance of Cichorium intybus–A review. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy. 2016;6(3):41-56.

- Imam KMSU, Xie Y, Liu Y, Wang F, Xin F. Cytotoxicity of Cichorium intybus L. metabolites. Oncology reports. 2019;42(6):2196-212.

- Rasmussen MK, Zamaratskaia G, Ekstrand B. In vivo effect of dried chicory root (Cichorium intybus L.) on xenobiotica metabolising cytochrome P450 enzymes in porcine liver. Toxicology Letters. 2011;200(1-2):88-91.

- Wang Y, Lin Z, Zhang B, Nie A, Bian M. Cichorium intybus L. promotes intestinal uric acid excretion by modulating ABCG2 in experimental hyperuricemia. Nutrition & Metabolism. 2017;14(1):38.

- Jana U, Sur TK, Maity LN, Debnath PK, Bhattacharyya D. A clinical study on the management of generalized anxiety disorder with Centella asiatica. Nepal Medical College journal : NMCJ. 2010;12(1):8-11.

- Puttarak P, Dilokthornsakul P, Saokaew S, Dhippayom T, Kongkaew C, Sruamsiri R, et al. Effects of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. on cognitive function and mood related outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):10646.

- Shinomol GK, Muralidhara, Bharath MM. Exploring the Role of “Brahmi” (Bacopa monnieri and Centella asiatica) in Brain Function and Therapy. Recent patents on endocrine, metabolic & immune drug discovery. 2011;5(1):33-49.

- Srinivasan K. Black Pepper and its Pungent Principle-Piperine: A Review of Diverse Physiological Effects. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2007;47:735-48.

- Han HK. The effects of black pepper on the intestinal absorption and hepatic metabolism of drugs. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 2011;7(6):721-9.